The Mexican-American war began in 1846 and lasted for nearly two years — depending on the ages of the soldiers, many of the troops who fought together during that war fought either with or against each other in the Civil War, which began about 14 years later in 1861.

As an example, Generals Ulysses Grant and Robert E Lee were allies in the Mexican war, and of course bitter arch rivals less than two decades later.

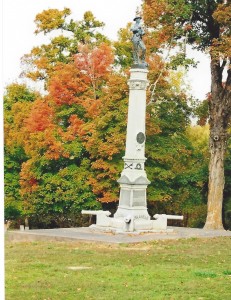

In a moment of pure luck, Lynn and I discovered a gentleman from the Ozarks who was a veteran in both wars: James Harrison Kay. He was born in 1817 (Lynn noticed that he was born only 18 years after George Washington’s death, which is kind of mind-blowing) and died in 1891; he’s buried in Coffelt Cemetery in Benton County, Arkansas:

Kay was born in Abbeville, South Carolina – when President Polk asked for volunteers to help win the Mexican war, James Kay answered the call at the age of 29 becoming a member of the South Carolina Palmetto regiment.

The prestigious Palmettos were the first regiment to storm the gates of Mexico City and to subsequently raise the American flag in victory.

At some point after the his valiant service in the Mexican War, Kay relocated to Mississippi — he became a 2nd Lt. in the Confederate Army, serving in the 17th regiment of the Mississippi Infantry –the regiment (nicknamed the Burnsville Blues) garnered high praise from General Robert E. Lee for meritorious service.

One of Kay’s fellow soldiers, Robert A Moore kept a diary of the regiment’s day to day activities up until he was killed in the Battle of Chickamauga (late summer, 1863)– this battle was probably the most notorious and bloodiest battle the 17th regiment was engaged in. In fact, the Battle of Chickamauga was the bloodiest battle in the Western theater — 13,000 troops were killed.

“Whoever controls Chattanooga Wins the War” — Abraham Lincoln

Lincoln’s opinion regarding a Chattanooga victory was based on logistical fact. Defeating Chattanooga would result in a “clear shot” all the way to Atlanta. A major rail hub, a disruption of supply lines to the confederates would also be possible. These reasons, plus the fact that Chattanooga was a banking, commerce and manufacturing center fueled Rosecrans [Union general] toward this ultimate goal.

Despite the fact that the Chickamauga “skirmish” was considered a Confederate victory, nothing was gained by the South. A determined Rosecrans ultimately took control of Chattanooga — the beginning of the end was near for the confederates. A footnote in Robert Moore’s diary describes the plight of the 17th regiment 2 years and some months into the war:

“. . .with some marching and countermarching, the 17th remained with Longstreet in East Tennessee, enduring great hardships. More than half of the men were at times barefooted and almost naked, when the weather was bitter cold and ground covered with snow.”

James Harrison Kay after the War

2nd Lt. Kay returned to Mississippi after the Civil War, no doubt a changed man – one of his sons was lost in battle and he had to begin the task of rebuilding a life for his family in the post Civil War south — a process complicated by the assassination of Lincoln. At one point after the War– sometime before 1880, he relocated to Arkansas, where he lived until his death in 1891. – just one of the many unsung heroes hidden in the Ozarks

Although it’s certainly not uncommon to locate gravestones of Confederate soldiers in Arkansas, it’s much less common to find a dual war veteran, such as James Harrison Kay.