Several weeks ago, President Obama attempted to right a wrong against veterans who were denied the Congressional Medal of Honor because they were black or hispanic.

The story reminded me of the angst and disquiet Lynn and I felt when we set out to locate a treasure that is not only hidden in the Ozarks, but largely forgotten: the Oaks Cemetery in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

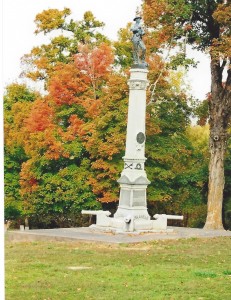

:

Cemetery History

The cemetery was established after the Civil War, and for many years was the only place African Americans in Washington County were allowed to be buried. With only one exception (more on this fascinating story in our next post), it is the only cemetery where former slaves are interred.

A good many of the graves are merely marked with a stone — others aren’t marked at all.

This grave is likely that of a former slave. Although the name of the person buried here is largely obscured, the birthdate is listed as 1801.

Murder in Tin Cup

One resident interred in an unmarked grave was Patrolman Lem McPherson, Fayetteville’s first African American police officer. McPherson’s beat was in Tin Cup, the black section of town. In late April 1928 as prohibition was drawing to a close, local bootlegger EB Williams was released from jail after a 9 month stint for his crimes of intemperance.

26 year old Williams had become paranoid, and once released from jail he plied his festering paranoia with more alcohol. Convinced that his wife had been having an affair with 48 year old McPherson, he set out to hunt him down.

After roaming the streets looking for the object of his hatred, Williams finally found and confronted McPherson; he shot him twice before stealing the victim’s service revolver — Williams eluded police for nearly a week before he was finally captured. He was ultimately tried and convicted of second degree murder and was sentenced to 21 years in prison.

Forgotten Soldiers

The Oaks Center is directly adjacent to the the south side of the Fayetteville National Cemetery, where local veterans and their wives are laid to rest. However, there are a number of black veterans who were not allowed the honor of being buried with their fellow veterans, even though their graves are located mere feet away. Not long after our trek to the cemetery, Obama honored vets who’d been overlooked because of race — in my own mind I was comforted by this and hoped that in some cosmic fashion the “less than” way black veterans and Officer McPherson were treated in the past was somehow atoned for; that maybe they know we are now aware of the injustice.